My Monroe Moment

an excerpt from my memoir, Saturday Morning

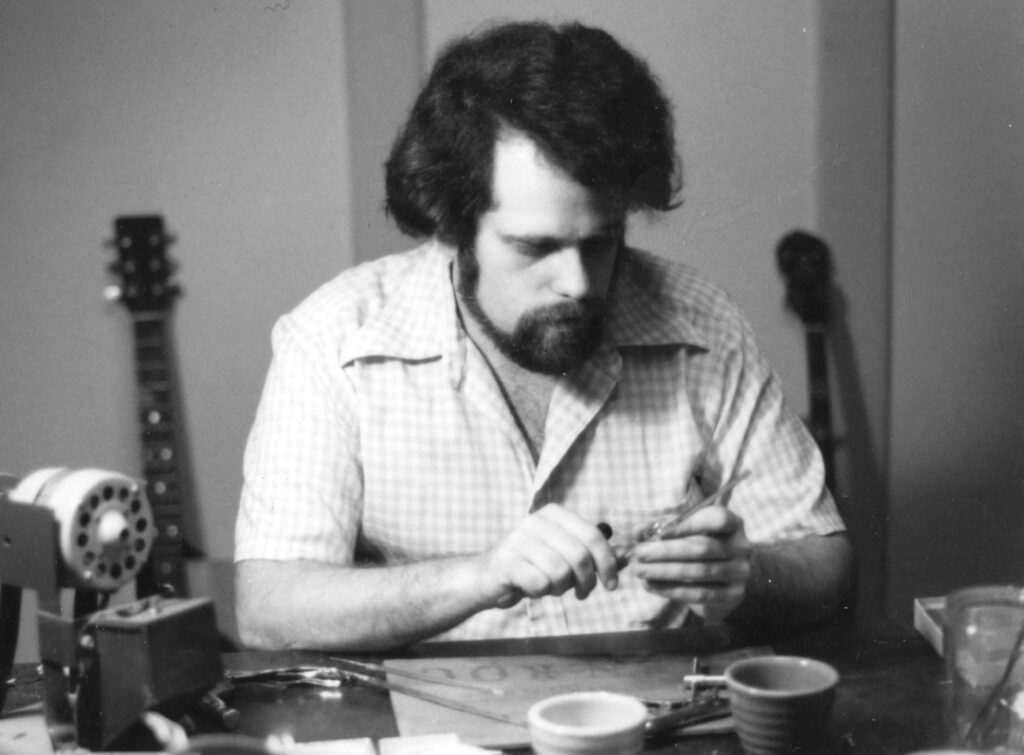

by Rick Shubb

For our first production run we made 100 fifth string capos. I packed most of them in a shoebox and planned a trip south. It was nearly summer, and there would be bluegrass festivals within a day’s drive of each other every weekend. Each festival would feature some top bands, and if I could sell one of my new 5th string capos to a few of the top banjo players, I’d be in business.

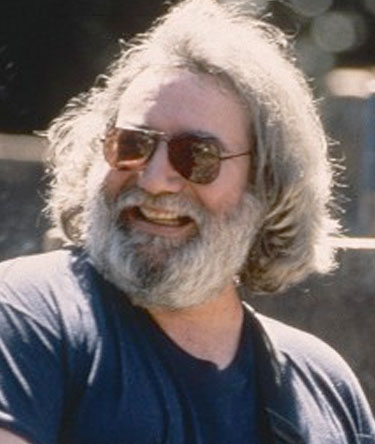

But before I hit the road, I made a few calls to local banjo players. The first to respond was my old friend and housemate from my Palo Alto days, Jerry Garcia. At that time Jerry was indulging his love of the banjo in the all-star bluegrass band, Old and In the Way.

So Jerry Garcia became Shubb Capos’ very first customer, and his rare and valuable Weymann banjo was my first installation. I was a bit nervous about the installation; I was still more comfortable playing a banjo than drilling holes in one, especially someone else’s, and I didn’t have a workbench or an array of tools; only the two hand held tools required for the job. If anything went wrong, I’d have no way to fix it. I’m happy to say that nothing went wrong, and in the weeks that followed I would become more confident about mounting the capos on expensive banjos.

I packed my VW squareback, grabbed my dogeared shoebox full of capos, and headed south. I had mapped out a trip that would take me to five bluegrass festivals in five weeks. My first stop was a festival in Knob Noster, Missouri.

I had been on the road for about three weeks, and the launch of the new capo was going well enough. I had managed to sell four or five at each festival, usually to players in top bands. Between festivals I was staying at a friend’s house in Nashville and one day he received a phone call that was for me. It was Buck White. He had heard through the grapevine that I was in town, and he needed a banjo player for some shows. Buck and I had met many years earlier at Carlton Haney’s Fincastle festival, where we had spent days jamming together. We hadn’t seen each other since, but he remembered me well from those jams, and didn’t require an audition. I remembered him well, and didn’t think twice before saying yes.

That night I went to the White’s home for a rehearsal, which went very well. My playing meshed with theirs nicely. When I’d picked with them years earlier Buck’s two daughters, Sharon and Cheryl, were pre-teenagers and just barely included in the band. For the short set they played at Fincastle, I’m not sure if the girls even went onstage. Now they, along with Buck, were the core of the band, and they were good. They were still going by the name Buck White and the Down Home Folks. They would soon change it to The White Family, which would finally be shortened simply to The Whites, but everyone around Nashville referred to them as Buck and the Girls. These days they are sometimes called the First Family of the Grand Ol’ Opry.

My first gig with them was a festival in North Carolina. It wasn’t one of the festivals that had been on my original itinerary, but this would work out better. I still was able to demonstrate and peddle my new capos, but now with added credibility. I wasn’t just some suspicious outsider from out west infiltrating the jams — I was Buck’s banjo man. I was onstage in a headliner band.

I extended the stay I’d originally planned by a week or two to play two more festivals and some club gigs with Buck and the girls. One of the gigs was at Randy Wood’s Pickin’ Parlor in Nashville. There has generally been one Nashville club at a time that was the happening venue for bluegrass, and at this time, this was it: knowledgable and attentive audiences, and a hub for the local musicians. Randy Wood was the top instrument repairman in town. His workshop was in back of the club.

There is a running gag about Nashville clubs, and how people in them are glancing at the door every few seconds to see who might be coming in. If you’d glanced at the door at the right moment on this evening, you’d have seen Bill Monroe come in.

Bill Monroe knew my face, but not my name. I had been to many of his shows, spoken with him several times, and even picked a few tunes with him at impromptu festival campsite jams. I was familiar enough to him that he would smile and nod when he saw me. If he ever had known my name, he had forgotten it, but that’s okay. He sometimes didn’t even get the names of his own band members exactly right, or made up new ones for them. He did let me sleep on his bus one night. Years earlier I had traveled to Los Angeles to hear him play for seven nights at The Ash Grove. I would stay at my uncle’s apartment in L.A., but on my first night in town I had not made that connection yet, and needed a place to sleep. The Bluegrass Special may not have been the most reliable vehicle (sometimes referred to by the band as the Bluegrass Breakdown), but the beds were fairly comfortable.

Monroe had come to the Pickin’ Parlor that night to check up on his mandolin that was in Randy Wood’s shop for some sort of repair. Buck and Bill knew each other well, and a few minutes after Bill had come in and approached the stage to say hello, Buck shook his hand and then handed him his mandolin, inviting him to sit in. Monroe took the instrument and stepped onto the stage, while Buck took a seat with some friends at a front row table.

This would be my one and only experience at playing onstage with Bill Monroe, and if I had scripted it, it couldn’t have been much better. The White sisters were as good a rhythm section as anyone could wish for, and I had chops from playing quite a bit with Buck and the girls. I was already in a good groove when Monroe stepped onto the stage to sing several of his best-known songs.

We played for about twenty minutes, and at the end he sang a long medley of up-tempo songs that he usually sings in the key of B. Only for some reason he happened to start in B flat, which meant that he was reluctant to play mandolin solos in the less familiar key. So after almost every chorus he would give me the nod for a banjo break. It was as if he was showcasing me, and I had the wind at my back. The tempo was like chocolate cake for the banjo. After the medley was over, he patted me on the shoulder, and then said to the audience “Now this boy is doing some mighty fine banjo picking, I can tell you that right now.”

And that was my Monroe moment. What more could a young banjo player wish for? I was never a Blue Grass Boy, as some of my friends had been — that dream of so many young players that was abandoned once a few years passed and sensibilities kicked in. I never did the all night bus rides or the part where you move the porta-potties at the festivals. My Bill Monroe experience may have been short, but it was sweet.