The Berkeley Fiddlers’ Convention

by Rick Shubb

There is a difference in intensity between east-coast and west-coast musicians that I call the East-Coast Edge. I can’t think of anything that illustrates this difference better than the Berkeley Fiddlers’ Convention.

There is a long established tradition of fiddlers’ conventions in Virginia, North Carolina, and other southeastern states. They predate the first bluegrass festivals by many years, and feature fiddle and banjo contests that award cash prizes and much prestige to the winners. Rules are very strict governing tune selection, and penalties given for any departure from traditional arrangements, right down to specific obligatory notes. The contestants are as obsessively competitive as beauty pageant queens. To their credit, these events have served to preserve old-time music, especially traditional fiddling, which I suppose may have been in some danger of going extinct. Still, the rigidity that stifles creativity and nurtures a gunslinger mentality is foreign to most west-coast musicians.

There was a lively old-time music scene in Berkeley in 1968, and we decided to have a fiddlers’ convention of our own, only we would do it Berkeley style. To begin with, no one was in charge. Several of us conspired to conceive the event, and forgive me if I have forgotten many who may have been key contributors. I know for sure that Hank Bradley and Eric Thompson were among the major conspirators, since I was in a band with them at the time, and their sense of humor was all over the thing. But practically everyone who played old-time music in or near the Bay Area was involved to some degree.

To inflate its credibility we dubbed it the 35th Annual Berkeley Fiddlers’ Convention. Of course everyone knew it was really the first one, but this set the tone of absurdity that would guide the event. It is amazing now to think back on how little planning, or money, or actual work was required to make this happen. It was a simpler time, when people could just do something without getting suffocated in red tape. All of us who did any legwork, such as it was, volunteered our time.

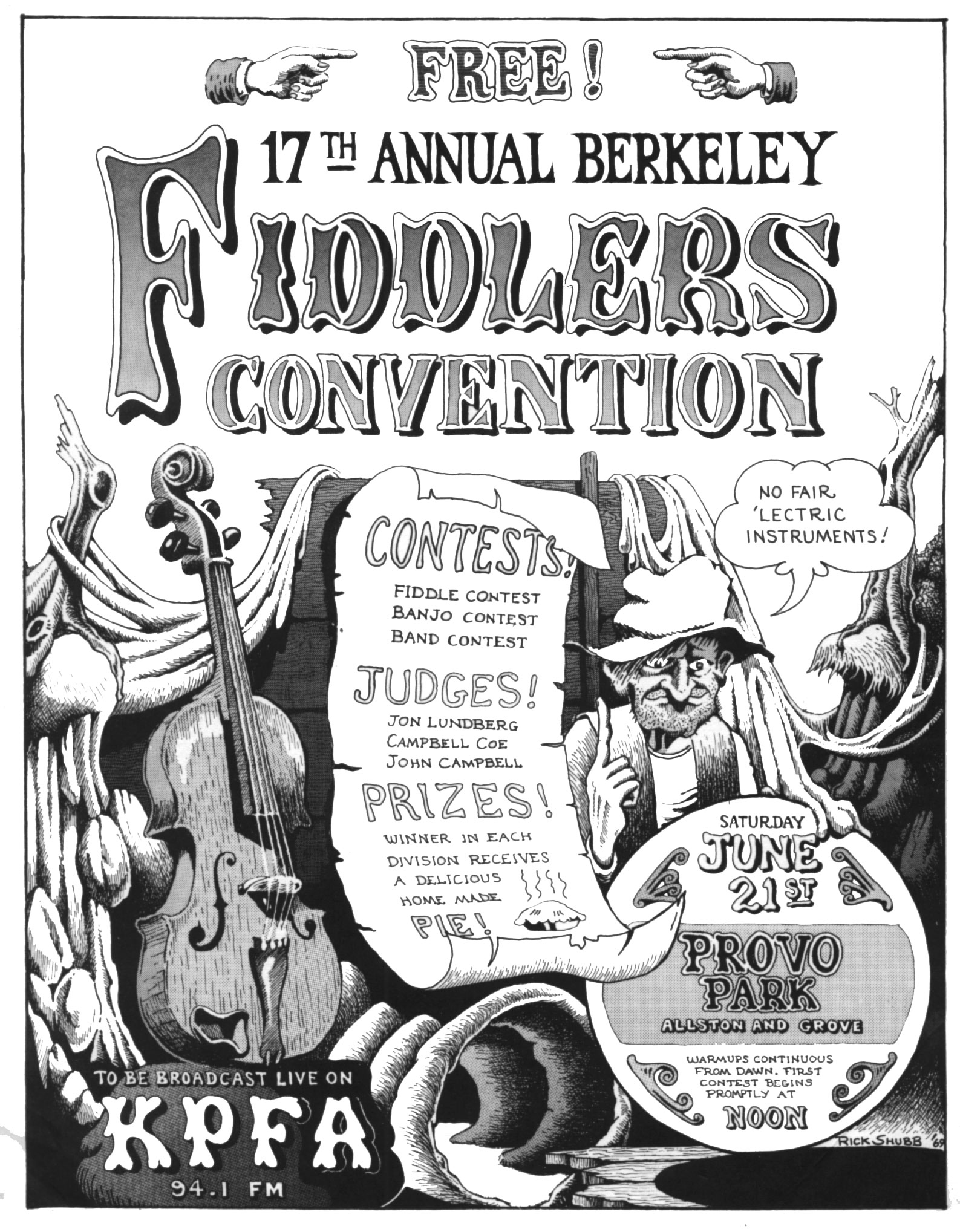

Hank Bradley created the poster for the first one. I would have, but I was swamped with my poster assignments from the Carousel Ballroom. I would do them for the subsequent two years. Someone had to obtain a permit for the use of Provo Park, and Eric Thompson volunteered. People at the city office kept asking him who was sponsoring the event, and he persistently tried to explain to them, “No one. We’re just going to do it.”

There needed to be sound reinforcement, and the sound crew from one of the local rock bands volunteered their labor and equipment. To make sure that everyone would get into the right spirit of the “contests,” first prize in each division would be five pounds of rutabagas. Second prize was six pounds of rutabagas.

Before the day arrived, it was already shaping up to be a party, and a parody of the eastern conventions. The best move of all was the selection of judges: Jon Lundberg, Campbell Coe, and Big John Campbell. Big John was a hot country guitarist, manager of Webb’s Music up in the delta region, and a suitably colorful teammate for the other two. There was definitely something to get here, a mood that had been suggested. The judges not only got it, they took charge of it, and carried it off beautifully.

Provo Park, bounded by the police station and Berkeley High School, was already established as a concert venue. The poster said, “Warmups continuous from dawn,” a phrase borrowed from one of the eastern conventions, but I think the only ones there at dawn were a few homeless people in sleeping bags. I arrived around 10:00 a.m., and other musicians were straggling in around that time, too.

As the startup time of noon approached, the park was filled with people. Admission was free. Signup for contestants was free. Some people insisted on making contributions, but there were very few costs to defray. Some people asked who was in charge, and the answer was “no one.” If there had been any problems, there would be no one to talk to. Only there weren’t any problems.

Shortly before noon the judges began to arrive. One at a time they made grand entrances like professional wrestlers or politicians; waving, shaking hands, blowing kisses, and the crowd took up the chant “Here come de judge, here come de judge,” as each entered. Jon Lundberg was especially resplendent, dressed to the nines in a classy vintage suit from the 30s and sporting an elegant walking stick. One of them placed a wooden box on the judges’ table, labelled Bribe Box, and announced that bribes were being accepted. Each specified his preferred brand of whiskey.

Richard Greene, west coast fiddler with an atypical east-coast edge, showed up. Fresh off a stint with Bill Monroe, and too much a heavyweight to be a contestant, he was added to the judging staff.

Throughout the day the judges would arbitrarily deduct and award points, although no point system had been established. With Gong Show ruthlessness they repeatedly disqualified contestants, often the best musicians. One large band was disqualified for unlawful assembly. One contestant had a beautiful antique violin, a predecessor to the modern instrument, which he played quite well. He was disqualified for not having a real fiddle. I was disqualified for something or another, but I took it as a compliment. It meant that they knew I wouldn’t be pissed off.

Most of us were trying to think up something zany to do. I only recall one contestant who was actually trying to win: banjoist Winnie Winston from New York City. You can’t blame him. First off, his name was Win-Win. But mainly, he was from NYC, and no one from NYC could possibly understand not trying to win. That East-Coast edge, you know. That morning he’d been warming up with Eric Thompson, who backed him up on guitar. He asked Eric what tune he should play, that might best impress the judges. Eric, clearer on the concept, just cocked his head and said, “Winnie … it’s rutabagas.” “Yeah, yeah,” said Winnie, shaking him off, “but what should I play?” He ended up winning first place, which is good. He would have been sad if he’d lost.

The judges awarded first place in one category to someone who was known on the scene, but who was in Switzerland at the time, pointing out that, “…nowhere in the rules does it state you must be present to win.”

Since there was no entry fee, no restriction on how many times an individual could participate, and no cutoff time for entry — in other words, no rules — many of us would assemble an impromptu group on the spot. All you had to do was to get word to the MC, Larry Hanks, that you wanted to play, and he’d get you in queue. Well, maybe it helped if he knew you. The judges would create new categories on the fly, and announce awards whenever they thought of them. I believe Hank Bradley won the Best Supporting Actor award.

We expected it to be a one-time event, but like a hit movie, it spawned two sequels. The following year everyone wanted to do it again, and why not? The only question that really came up was, what do we call it?

We expected it to be a one-time event, but like a hit movie, it spawned two sequels. The following year everyone wanted to do it again, and why not? The only question that really came up was, what do we call it?

The first one had been the 35th annual. We immediately ruled out 36th as dull. I once saw a panel discussion on television, in which comedy writers discussed writing for Sid Caesar. With one week in which to write a 90-minute show, they spent an hour arguing over what would be the funniest number on a roulette wheel to bet on. They settled on 32. We went through a similar process in deciding what to call the next two Berkeley Fiddlers’ Conventions. If we went a lot higher than 35th, it would suggest we were rapidly hurtling into the future. If we went too low, it would lack the venerability we’d sought with 35. We went with the 17th Annual. Yep, that was the funniest number.

Then the third year, faced with the same task, it seemed that we should pick a number between the previous two, to neither imply forward nor backward movement through time. Since the first two were odd numbers, we landed on the even, and called it the 22nd Annual Berkeley Fiddlers’ Convention. 22 might not be as funny as 17, but it was the best we could do with what we had to work with.

As with movies and their sequels, the first usually being the best, I’d have to say that the first …I mean, 35th Annual Berkeley Fiddlers’ Convention, was the best. But the other two were pretty damn good, too, and almost as good as the first. The same core of three judges presided over all three events. Prizes in the 17th Annual were homemade pies. First prize in the 22nd Annual was an all expenses paid trip to Emeryville, a not-very-glamorous industrial town that borders on Berkeley. The prize consisted of two bus tokens and a certificate for lunch at the Doggie Diner.

So if they were still fun, then why did they not continue? I think it just lived out its natural lifespan. It may be because some of the key participants had moved by then, or were traveling in 1971. Plus, there were various outside pressures creeping in: proposed sponsorships, involvement by the city itself, filming, TV coverage, all things that would have changed it too much. So since no one had ever been in charge, no one pulled the plug. It just didn’t happen any more.

Years later there was some discussion of having another one, and I think it might have worked. It would have been the 1st Annual Berkeley Fiddlers’ Convention, and it would have been in Seattle.

During the past few years I’ve been writing my memoirs, which I’ve titled Saturday Morning. This is a chapter from that work. If you’d like me to post more excerpts from it, or if you’d like to see the entire work published in some form, let me know: shubb@shubb.com

also of interest: Rick’s Cafe | Rick Shubb, musician | graphic artist