also of interest: Rick Shubb, the graphic artist

Someone once commented to Doc Watson about his Shubb Capo. Doc replied, “Son, I knowed Rick Shubb before there was a Shubb Capo.”

Someone once commented to Doc Watson about his Shubb Capo. Doc replied, “Son, I knowed Rick Shubb before there was a Shubb Capo.”

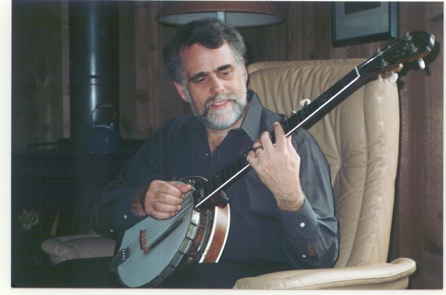

He was right. If you know my name, it is probably because of my capo. But before that I made my living as a 5-string banjo player and teacher, and occasionally as a freelance graphic artist. This page is for those of you who may be curious about my career as a performing and recording musician.

First, here are some sound files to listen to. Scroll down for the rest of the story.

Apanhai te Cavaquinho with Raul Reynoso, circa 2007

Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, with Bob Wilson and Charlie Warren, from the CD “Bodega Sessions,” circa 1999.

Prisoner’s Song, with Vern and Ray, from the LP “Sounds from the Ozarks,” circa 1974.

I Don’t Love Nobody with Hank Bradley and Doc Watson, circa 1968.

My first interest in playing music was sparked at age 15 by my brother Bill, seven years my senior. He was going to college at U.C. Berkeley, where folk music was getting popular. He had a good guitar; a Martin 00018, which he played finger style, and had a pretty nice touch. He also had just gotten an inexpensive open-back banjo, which he wasn’t doing much with.

Bill had taught me a little guitar, but I was not very motivated to progress on it until one day when we both discovered a record of Merle Travis. For the next year we both were trying to play as much like Travis as we could, but much of it remained a mystery.

One year later I heard a Flatt and Scruggs LP — Foggy Mountain Jamboree — that changed my life. Bill had not given me permission to play his instruments, but I began sneaking into his room when he was out in the evenings at the library studying, and started figuring out a rudimentary version of a 3-finger roll on his banjo. When he finally discovered me (betrayed by pick marks on the banjo head) I expected him to chew my head off. Instead, he was impressed with my right hand roll. It was the first time in my life that I’d outdone my big brother at anything, and that inspired me. Before long I had my own banjo; not a great one, but good enough to learn on, and I was off to the races.

In 1960 only a handful of people in the Bay Area knew what bluegrass was, let alone tried to play it. I was fortunate to meet a kid my own age, Sandy Rothman, who played banjo and guitar and was at the same place as me on the learning curve.

For about three years we were inseparable, hanging out together almost every day, talking about, listening to, and playing bluegrass music. We’d play for anyone who would listen, at every opportunity.

During that same time period I did some playing with a group called the Clovis County Country Boys. Here is a picture my Mom took off the TV set, with me playing on the Blackjack Wayne Show. I was fifteen at the time, although I look younger (and scared to death) in this picture.

We played every Saturday afternoon on TV, and then later that same night at a dance hall called the Dream Bowl that featured top country stars. We were the opening act, and quite frankly, we were amateurs and in way over our heads. But we felt like big shots at the time, playing on TV and hobnobbing with pros.

When Sandy Rothman headed east with Jerry Garcia, both seeking genuine bluegrass in its native habitat, I was in search of musicians to play with. I contacted Vern Williams, half of the powerhouse bluegrass vocal duo, Vern and Ray. I coaxed them out of retirement, and played some gigs at coffeehouses and festivals around Berkeley. But I was still a novice player, and overmatched musically. I was soon replaced in that band, but would reunite with them a few years later when my playing had greatly improved, and I was then a better match for them.

In 1966 David Grisman moved to California. I had met him a few months earlier on his initial west coast visit, and we had done some playing together. He asked me to form a bluegrass band with him. This became the Smokey Grass Boys, first with Bert Johnson on guitar, later replaced by Herb Pedersen. For about six months we played at a coffeehouse in SF once a week, and at the Jabberwock, a folk club in Berkeley, once or twice a month. During this time Grisman was formulating the foundation of his uniquely personal Dawg Music, and although we played straight bluegrass onstage, we had a few mandolin and banjo duets that were harbingers of things to come.

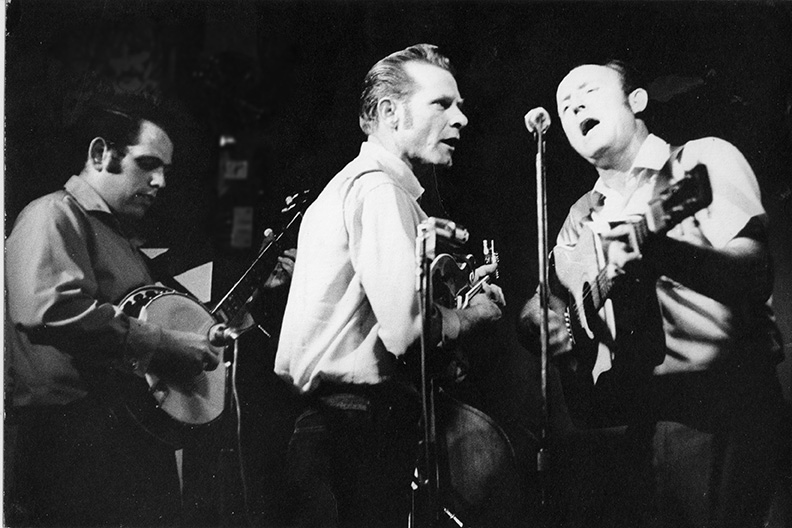

In 1967 at Sweet’s Mill, a famous folk music retreat in the foothills of the Sierras, oldtime fiddler Hank Bradley introduced me to Doc Watson. We had a long jam session in which we played just about every fiddle tune we could think of. Doc liked the way we sounded together so much that he invited us to join him on his west coast tour. He was performing as a solo at the time, and at the end of each of his sets, he would bring Hank and me up to the stage for three or four fiddle tunes. We even recorded a demo tape of about a dozen tunes, which he submitted to his record company, Vanguard, as a proposed album. They rejected the idea, and I understand their decision; Doc was not featured as prominently as they wanted him to be. Too bad for me and Hank, as it would have been quite a feather in our caps. A couple of selections from that tape are included here.

In 1967 at Sweet’s Mill, a famous folk music retreat in the foothills of the Sierras, oldtime fiddler Hank Bradley introduced me to Doc Watson. We had a long jam session in which we played just about every fiddle tune we could think of. Doc liked the way we sounded together so much that he invited us to join him on his west coast tour. He was performing as a solo at the time, and at the end of each of his sets, he would bring Hank and me up to the stage for three or four fiddle tunes. We even recorded a demo tape of about a dozen tunes, which he submitted to his record company, Vanguard, as a proposed album. They rejected the idea, and I understand their decision; Doc was not featured as prominently as they wanted him to be. Too bad for me and Hank, as it would have been quite a feather in our caps. A couple of selections from that tape are included here.

Florida Blues, with Hank Bradley and Doc Watson, circa 1967

Still buzzing with momentum from our stint with Doc, Hank and I teamed up with guitarist Eric Thompson and his first wife, Sue, to form the Diesel Ducks. The fiddle tunes were still the mainstay of our repertoire. This band did not have a long tenure, but we did once play a set at the Carousel Ballroom between Chuck Berry and the Grateful Dead, and we played a large role in creating the legendary Berkeley Fiddlers’ Convention.

The primary musical partnership of my life has been with guitarist Bob Wilson. Introduced by mutual friend Herb Engstrom, who “thought we would sound good together,” Bob and I were coming from diverse backgrounds, but we were both fascinated by the blend of our styles. Unlike other groups I’d played in, whose practices were driven by the need to compile a repertoire for performances, Bob and I were more interested in finding out what we could do. So we would sometimes play the same song for hours, exploring and rearranging. We had played together for a few years — for fun — before we ever thought of performing.

The primary musical partnership of my life has been with guitarist Bob Wilson. Introduced by mutual friend Herb Engstrom, who “thought we would sound good together,” Bob and I were coming from diverse backgrounds, but we were both fascinated by the blend of our styles. Unlike other groups I’d played in, whose practices were driven by the need to compile a repertoire for performances, Bob and I were more interested in finding out what we could do. So we would sometimes play the same song for hours, exploring and rearranging. We had played together for a few years — for fun — before we ever thought of performing.

Eventually we did get out of the house, playing frequently at the Freight and Salvage in Berkeley, various other clubs, and notably at the Blitz-Weinhardt bluegrass festivals in Oregon, where we recorded a live LP in 1976.

SHUBB, WILSON, and SHUBB …LIVE. (1976)

In 1999 we released a CD, Bodega Sessions, recorded in my home studio. And we have enough practice tapes to release a couple more, if I ever get around to sorting through them.

.

Avalon, with Bob Wilson, from the CD Bodega Sessions

During the 70s bluegrass gained in popularity in the Bay Area; there were several working bands, and a few venues where they could play. I was a charter member of High Country, Butch Waller’s band that is still going strong today.  At that same time I was starting a second stint with Vern and Ray, which would be far more satisfying than my first go-around with them. By this time I could provide a strong instrumental lead to augment their world class bluegrass harmony. I played with them off and on for a couple of years. We played at coffeehouses and festivals, and did a few west coast tours, one of which took us to BC, and we recorded an album, Sounds of The Ozarks, on Old Homestead Records. But their playing schedule could be sparse at times. That, as well as personal differences, caused me to start paying more attention to leading a band of my own.

At that same time I was starting a second stint with Vern and Ray, which would be far more satisfying than my first go-around with them. By this time I could provide a strong instrumental lead to augment their world class bluegrass harmony. I played with them off and on for a couple of years. We played at coffeehouses and festivals, and did a few west coast tours, one of which took us to BC, and we recorded an album, Sounds of The Ozarks, on Old Homestead Records. But their playing schedule could be sparse at times. That, as well as personal differences, caused me to start paying more attention to leading a band of my own.

Train 45, with Vern and Ray, circa 1971

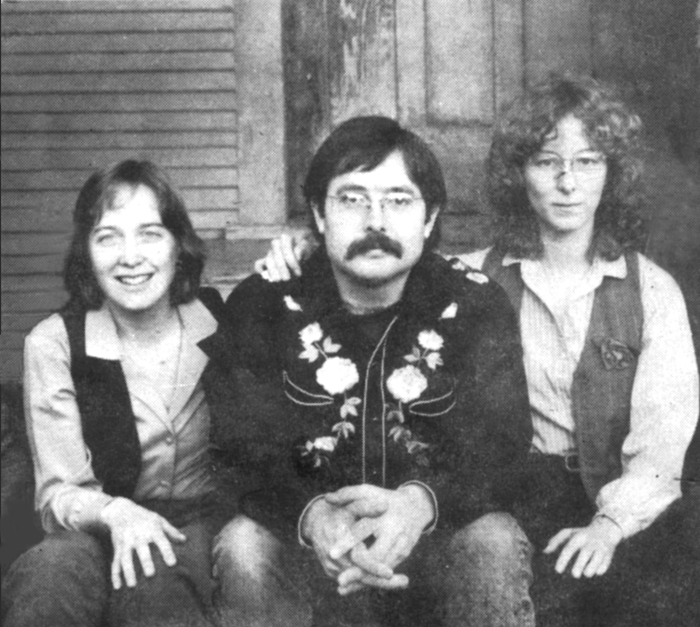

My club band was called The Hired Hands. The nucleus was me and my first wife, Markie, first on bass and later on mandolin. For a while we had rotating personnel that included Paul Shelasky, Brantley Kearns, Pat Enright, Dick Stanley, Bert Johnson, John Cooke, and others. But we finally settled on Rich Wilbur, guitar and lead vocal, with Markie switching to mandolin and her brother, Mike Sanders, on bass. In this form, with occasional guest fiddlers, we held forth at San Francisco’s famous Paul’s Saloon, two nights a week for two years.

Sioux City Sue, The Hired Hands, Rich Wilbur, vocal. circa 1973.

During the 70s the banjo became popular as a background instrument in commercials, and I found myself suddenly in demand for studio work. I did numerous commercials, on most of which I was barely audible in the mix … but I was handsomely paid. During that same period I also played on soundtracks for some movies, including Steelyard Blues, Thunder and Lightning, and Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, as well as some LPs by Robert Hunter, Shel Silverstein and others. Here is a track I’m on from Eric Thompson’s 1978 album, Bluegrass Guitar.

Stoney Creek, with Eric Thompson, David Grisman

I spent most of the summer of 1973 in Nashville, going out to bluegrass festivals each weekend to introduce my new 5th string capo. While in town midweek I got a call from Buck White, who needed a banjo player for some gigs.

He remembered me from the 1966 bluegrass festival in Fincastle VA, where we had done a lot of jamming together, and our playing styles had meshed beautifully. His memory of those sessions from seven years earlier was enough to get me the gig.

When I had jammed with him in ’66, his two daughters were not yet part of his band. But by ’73, they were a big part of it. They still went by the name Buck White and the Down Home Folks, but everyone referred to them as “Buck and the Girls.” Nowadays the Whites are known as “the first family of the Grand Ol Opry.”

These people were a pure joy to play music with. Their tight, relaxed rhythmic groove made playing easy, and Buck’s mandolin inspired me to pull out some of my swing licks I’d developed with Bob Wilson. I extended my stay in Nashville for a few weeks, and played a few festivals with them; it was one of the most enjoyable times I’ve had in music.

We were playing a midweek club gig in Nashville when who should walk in but Bill Monroe. Buck beckoned Monroe onto the stage and handed him his mandolin. Bill accepted, and took over the stage, leading Cheryl, Sharon, and me through a full set of his songs. Following a long medley of Monroe hits, on which he really ran me through my paces, he put his hand on my shoulder and announced “Now this boy is playing some mighty fine banjo, I can tell you that right now.” It was my one and only experience onstage with Bill Monroe, and it couldn’t have been better.

For a more detailed account, see “My Monroe Moment.”

In 1975 I moved to Portland, Oregon, where I played in a band called Dr. Corn’s Bluegrass Remedy. We played at a local club once a week, plus quite a few college gigs. We also managed to get onto network TV when the Today Show visited Oregon in 1976.

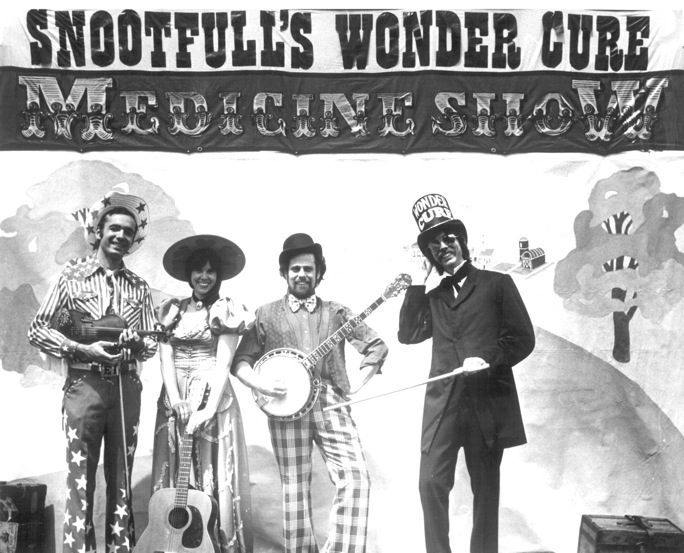

During my two year stay in the northwest I got to sit in with most of the local bands, including Good ‘n Country, the Sawtooth Mountain Boys, and the Muddy Bottom Boys. But the group I really clicked with, and which I joined up with for a short stint, was the Old Hat Band in Seattle. Besides being an old-time music trio, they each had self-created alter egos which they featured in Snootful’s Wonder Cure Medicine Show: a corny piece of vaudeville that was a barrel of fun. To participate in the Medicine Show, I created a character named “Honest Willie Cheatham,” banjo wizard and former town drunk of Gnawbone, Indiana.

In 1977 I returned to California, and did some playing with talented singer/guitarist Rob De Witt. We were hanging out and picking just about every day. It was an especially prolific period for me, and we were putting a band together simply called the Rick Shubb Band, that would mainly feature my own original tunes. We played only a few gigs, but then the life of this band was cut short as I neared completion of my new guitar capo, which would demand my undivided attention.

By the early 80s the Shubb Capo for Guitar had changed my life. While my passion for playing was as strong as ever, I knew a good thing when I saw one. The banjo took a back seat to the capo, as I set about learning to be a businessman.

I would have one more chance to feel like a working musician for three weeks, though. My old friend Laurie Lewis had booked a tour for her band, the Grant Street String Band, but learned that their regular banjo player could not make it. She asked me to fill in. The capo business was not yet so demanding that I could not take some time off, and so off I went.

I would have one more chance to feel like a working musician for three weeks, though. My old friend Laurie Lewis had booked a tour for her band, the Grant Street String Band, but learned that their regular banjo player could not make it. She asked me to fill in. The capo business was not yet so demanding that I could not take some time off, and so off I went.

We played gigs around the north coast of California, Oregon, Washington, and spent a week in British Columbia. It was like a vacation for me; the music was really good, as was the fellowship, and all I had to do for three weeks was play the banjo. For my last hurrah as a touring musician, I couldn’t have asked for more.

High on a Mountain, with Laurie Lewis, vocal

In the early 90s I had an injury to my left hand, and was unable to play for nearly two years. If you’re a musician then you know that coming back from a two-year layoff would be almost like starting over again. I had nearly decided to call it quits, and I was content with that decision, but some of my friends were set on talking me out of it. Or I should say, back into it. Chief among these was Raul Reynoso.

Along with Bob Wilson and Hank Bradley, Raul Reynoso has been one of my most consistent, longtime music partners. Although we have never been “officially” in a band together, we’ve managed to perform together dozens of times, and over the years we’ve developed a repertoire of specialty tunes. He’s been a member of my trade show team almost from the beginning. His playing is always an inspiration to me, and I try to never miss a chance to play music with him.

Along with Bob Wilson and Hank Bradley, Raul Reynoso has been one of my most consistent, longtime music partners. Although we have never been “officially” in a band together, we’ve managed to perform together dozens of times, and over the years we’ve developed a repertoire of specialty tunes. He’s been a member of my trade show team almost from the beginning. His playing is always an inspiration to me, and I try to never miss a chance to play music with him.

During my layoff from playing, Raul had become a member of a prestigious northern California club with an affinity for the performing arts, especially music. He wanted to share the experience with me, and invited me as his guest. The prospect of keeping in closer touch with Raul and some other world class musicians who were frequent guests or members convinced me to pick up the banjo and try to regain some of my old chops. It took years, as Raul patiently coaxed me back into shape, but eventually my playing was a reasonable facsimile of my former self.

In 2017 Raul and his wife moved to Northern California, and I quickly enlisted him to work for Shubb Capos, handling artist relations and customer support. He’s a natural born good will ambassador.

Valse de Bamboula, with Raul Reynoso and David Jackson

Whenever possible I have tried to play with musicians who are better than me. It’s one of the best ways to improve, and it certainly makes the musical adventure more exhilarating. I don’t perform very often these days, but I do try to keep my hand in. And as per my own advice to students, I keep the banjo out of its case.

Also of interest: My Banjo | Bodega Sessions (CD)